All doctors are responsible for their own education however, they must understand the needs of patients and how to contribute to the safe practice of medicine within the organisation where they work. At the same time, doctors must appreciate that 'education' and 'service delivery' are inextricably interrelated, hence they are learning in the workplace through supervised service delivery. This requires them to manage their learning needs in the context of their clinical work. They should understand the complexities, constraints and opportunities that they find in their practice and be able to choose how to make best use of these. Doctors also need to understand that, as well as engaging in more formal educational activities, they learn by working with other team members and seeking out feedback from senior colleagues in supervised learning events (SLEs).

Good educational practice acknowledges the private and public aspects of professional development and gives due importance to the key relationships which inform professional development. Effective learners will achieve their aims, acknowledging who they are and what they believe affects what they do. Foundation doctors do not live in a vacuum; they may have personal and family difficulties and the most effective learners recognise the impact of these factors and develop as a result of them.

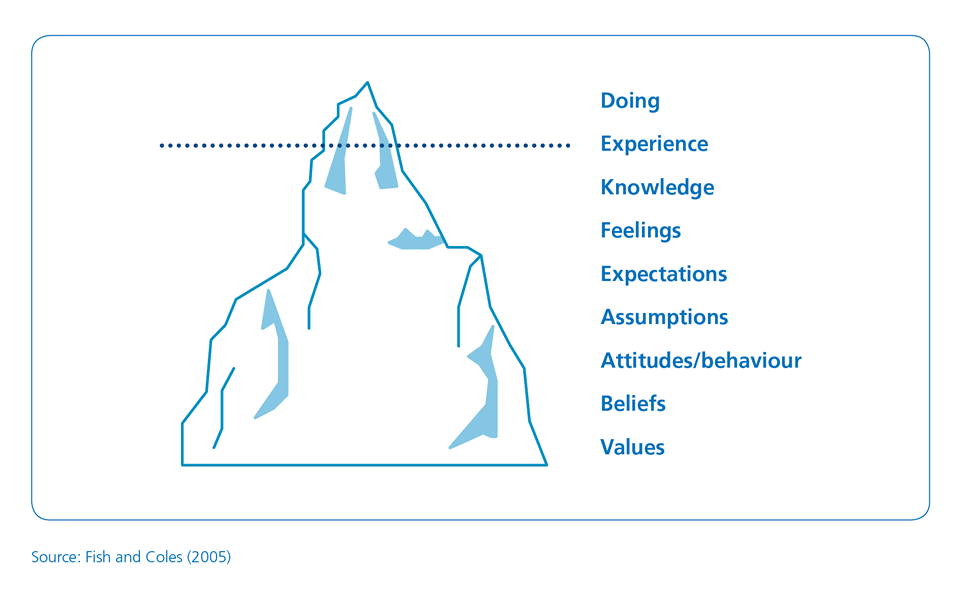

Effective educational practice will help foundation doctors to understand the relationship between theory and reality, which will enable them to exercise better judgement in complex situations. They will also be encouraged to understand other roles within the team and show how they can adapt and collaborate in emergency situations. Foundation doctors will need to become aware of the different perspectives and expertise that can improve problem solving, clinical reasoning, patient management and decision-making. This depth of understanding and expertise requires study and practice of all the components of professional activity, as outlined in the metaphor of the iceberg (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Developing a curriculum for practice

Source: Fish and Coles (2005)

Acquiring expertise that can be adapted to new situations depends on the development of clinical and ethical reasoning and professional judgement. The majority of learning occurs in teams and much knowledge and expertise is found in groups rather than individual practice. This strengthens the principle that learning in the foundation programme should take place in team-based practice. Expertise is more than knowledge or a toolkit of skills. The foundation doctor will learn similar skills in different settings, facilitating the development of transferable skills.

Doctors at the start of their careers, seek predictable solutions rather than acknowledging the paradoxes and ambiguities of clinical practice. The following actions should be considered:

Similarly, the acquisition and application of skills and knowledge will vary according to where care is given. Placements in general practice will enable foundation doctors to care for acutely ill patients and those with long-term conditions in a different context to secondary care. Patients will present differently and their illnesses may be seen at a much earlier stage or during quiescent or maintenance phases. Their management will need different clinical and risk assessment skills. Also, primary care offers a unique perspective on how secondary care specialties work. Foundation doctors will be able to follow their patients through the service, from the presentation of acute illness through investigation, diagnosis and management to recovery, rehabilitation or death. They will also be able to see the effect of acute illness on those with a long-term disease.

Consideration will need to be given regarding how rotations for foundation doctors should be organised to ensure the access to and development of a range of clinical skills across a variety of clinical situations. Some posts will offer a wider range of clinical experiences than others, for example, meaningful experience in child health can be acquired in general practice or the emergency department and a paediatric placement may not be necessary. Every rotation must comprise a suitable blend of placements, each of which can deliver the curriculum outcomes.